environmental Strategist, between the lines: Legionnaires Disease is a bacteria that can create an environmental liability for those using central air conditioning systems, fountains, room-air humidifiers, ice-making machines, whirlpool spas, water heating systems, showers, misting systems typically found in grocery-store produce sections, cooling towers used in industrial cooling systems, evaporative coolers, nebulizers, humidifiers, windshield washers….

A little background: Legionnaires is a bacteria that got its name after a 1976 outbreak at an American Legion Convention in Philadelphia. 221 people contracted the bacteria and 34 died.

What risk management strategy are you implementing to address exposure to Legionnaires Disease for your client’s? Pollution liability insurance can protect property owners or those with an insurable interest for their exposure to Legionnaires.

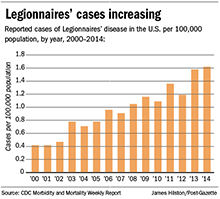

Legionnaires’ cases in the United States quadrupled from 2000 to 2014, with about 5,000 people a year — and probably many more — now being infected by the deadly form of pneumonia, but the exact reason for the growth is unclear, officials with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday.

And too many of those cases occur during an outbreak, CDC Director Tom Frieden said Tuesday in a phone call with reporters to announce the publication of a comprehensive study on outbreaks published on the CDC’s Vital Signs webpage.

“I’ll give you the bottom line [of the study] right off the top: Almost all Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks are preventable with improvements in water system management,” he told reporters.

During that 15-year period of 2000 to 2014, the CDC investigated 27 confirmed, land-based — as opposed to ship-based — Legionnaires’ outbreaks.

Those outbreaks included the 2011 and 2012 Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System that the CDC determined infected 22 people and led to the deaths of six of them. Overall, 415 people were infected in the 27 outbreaks, and 65 of them died, the CDC said.

The CDC study found that in 23 of the 27 outbreaks it investigated there were “gaps in maintenance that could be addressed with a water management program to prevent Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks…”

There were many more people sickened and killed during other outbreaks the CDC was unable to investigate during that timeframe. It noted in the study that from just 2000 to 2012, it had requests to investigate about 160 outbreaks.

CDC officials said this new study was prompted by two factors: First, the public notoriety of cases over the last three years that included, first, the Pittsburgh VA, then a cooling tower outbreak in New York City, and, last year, the outbreak in Flint, Mich.

In addition, last summer, after nearly a decade of work, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers — known as ASHRAE — completed its recommendations for dealing with the water-borne disease of Legionella in building water systems. ASHRAE’s recommendations are expected to eventually find their way into many of the country’s state or local building codes, carrying the power of law.

Since last summer, though, the CDC “heard the ASHRAE standards weren’t easy to understand unless you were a building engineer,” Dr. Frieden said.

As a result, the CDC on Tuesday also released an online “Toolkit” that it hopes will make adopting the ASHRAE standards easier for building owners and managers.

The Toolkit was piloted in Flint, where the CDC took it to building owners and managers who were impacted by the outbreak there that infected 91 people — including 50 cases in a local hospital.

In addition to the few, widely publicized outbreaks that occur annually, the CDC said it is equally concerned about the overall rise in Legionnaires’ cases, with more than 5,000 annually, nearly all of which occur without little to no publicity.

“And we think [the number of people infected] is much higher,” said Cynthia Whitney, co-author of the Vital Signs study, “not because we don’t hear about the cases, but because we believe they’re never diagnosed.”

The number of cases may be rising steadily for a variety of reasons, she said, including: More healthcare professionals know to look for it; better testing; a larger, more vulnerable and aging population; and a warmer climate that makes it easier for Legionella — the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease — to grow.

Victor Yu and Janet Stout, two Pittsburgh-based Legionnaires’ experts who were not involved in the CDC study, noticed in the Vital Signs report, however, that the CDC said nothing about regularly testing a building’s water for Legionella, something they have recommended for 30 years.

“The CDC has a long history of recommending not looking for Legionella as a prospective element to assess risk,” Dr. Stout said.

The CDC has said for decades that it believed testing regularly for Legionella would give building owners a false sense of security since people have contracted the disease when there were no signs of the bacteria in the water system.

Dr. Whitney said there is no testing recommendation in the Vital Signs study because “we didn’t want to get into it.”

But she said because the ASHRAE standards now recommend testing water, the CDC has now changed its position on testing since last summer.

“We are not against testing” water for the presence of Legionella, she said. “We think it has its place, particularly in healthcare facilities.”

Sean D. Hamill: shamill@post-gazette.com or 412-263-2579 or Twitter: @SeanDHamill.

First Published June 8, 2016 12:00 AM